I’m new to Harry Crews.

The Southern writer (1935-2012) taught many years at the University of Florida and is associated with the post-Faulknerian genres known as Dirty South or Grit Lit.

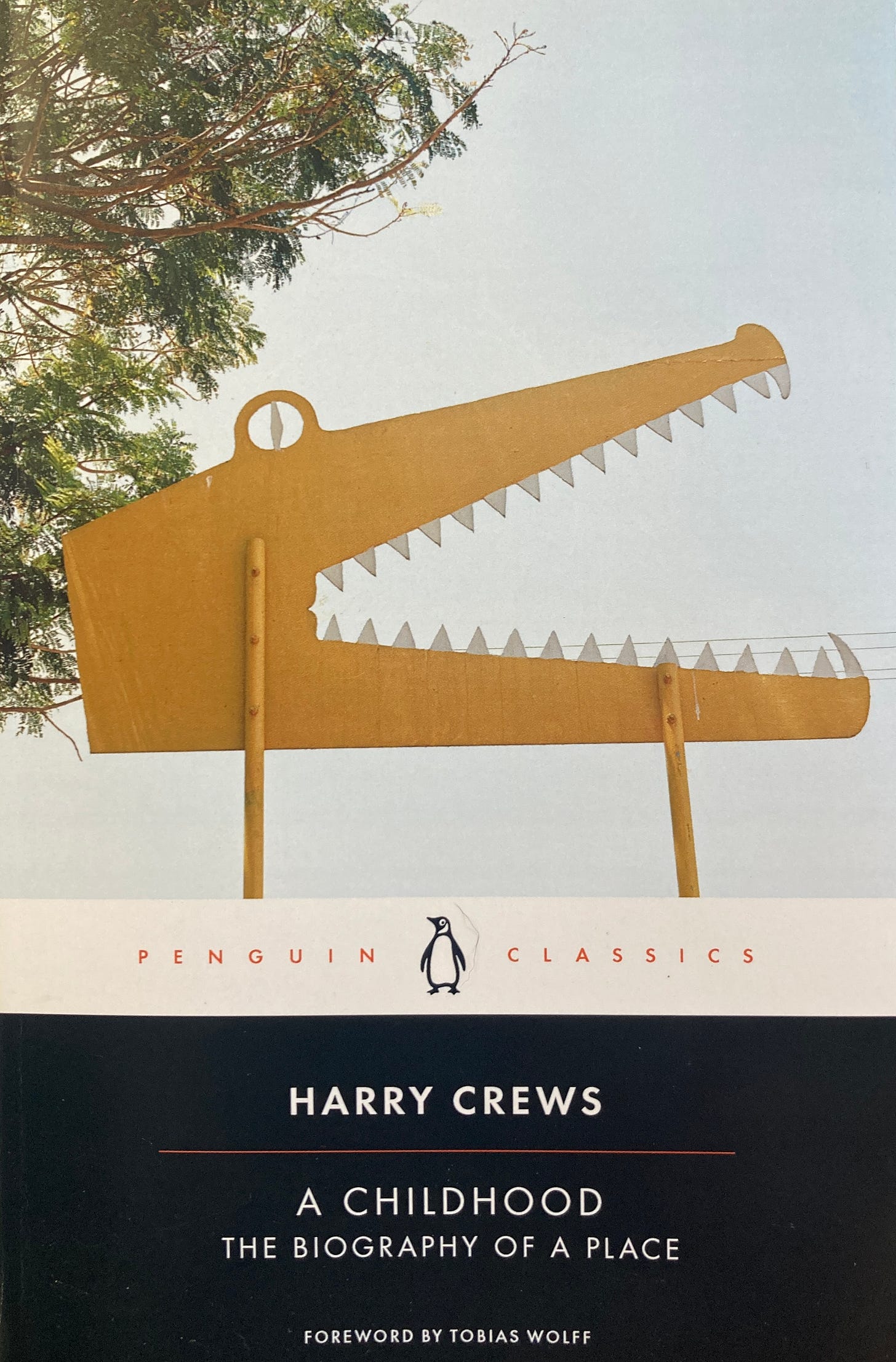

I’m less than halfway through his memoir, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, which recounts his boyhood in rural, poverty-stricken Bacon County, Georgia.

His father works himself to death on the farm. There’s whiskey, shimmering heat and family feuds. One of Crews’ first memories is going over to eat at the home of the Black family they work the land with. The main course is possum, which has been scalded, scraped and gutted. The eyes are taken and set in a dish.

Because I was company, Auntie gave me the best piece: the head. Which had a surprising amount of meat on it and in it. I ate around on the face for a while, gnawing it down to the cheekbones, then ate the tongue, and finally went into the skull cavity for the brains, which Auntie had gone to some pains to explain was the best part of the piece. (Pg. 66)

He neglects to tell us how it tastes.

But there is something spiritual about eating a possum which, as Crews points out, lives by eating rotten animals, which is why his own “mama” doesn’t cook them.

After dinner, Auntie takes young Crews, who is only about five or six years old, out back with the possum’s eyes. They dig a hole and bury them.

“Know how come you got to barum?” she said.

“How come?” I said.

“Possums eat whatall’s dead,” she said. Her old cracked voice had gone suddenly deep and husky. “You gone die too, boy.”

Gritty indeed.